Programming a building may seem like a simple task to anyone who has ever been inside of building (I hope everyone) and to a modern designer, the task may seem even simpler. Follow in the footsteps of architecture's great

Louis Sullivan, and his "form follows function" campaign and everything works.

One problem with this philosophy, form doesn't always follow function. Especially during today's hard economic times, where architects seem to be working on more adaptive reuse projects than new buildings. Architects are facing an era of re-programming building with functions that were never conceived of when the form was generated. Whether in a church converted into condos, a factory into working studios for artists / designers or simply reconstructing the corner store back into a trendy hang out for young people, the idea of program is being given a new look.

For me, when I think of programming, I want my architecture to RESPOND to the existing conditions. Sometimes (in new construction) Mies' ideas are still very applicable. Whether the opportunity calls for a cultural, architectural or economic response to a site, I would like to break each step into stages that look at things from two points of view [1. the practical response 2. the opportunity to do something fun and creative.]

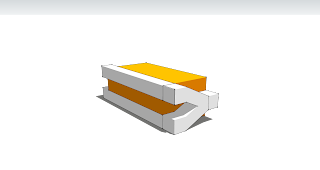

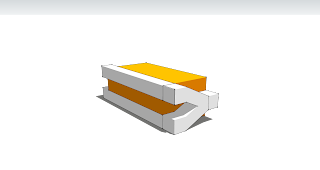

Below you find a series of diagrams that attempt to touch on this very idea in a new construction:

1. The program as presented by a client, competition or any number of unpredictable situations. Here the form is what it is. Nothing more than the bare minimum example of architecture.

2. The given program in response to interior activity: here I am looking at ways in which the form of the building can begin to subtract masses where program deems appropriate. Usually this gesture will respond to a number of site forces. Here there are no "real" forces so architectural gestures reduced to hypothetical activities such as that of a school or office.

3. Isolating again, the next form of program found in all buildings: circulation. Here I am taking a literal response to how one may move through a building that has three floors and two forms of egress.

4. In this diagram, I am visualizing ways in which both ideas can come together to express a single expression of activity and circulation programming that works with a synergy of function.

5. Here, we are looking at my program expression faced with issues of adjacency of neighboring program, probably of a completely separate function.

6. Finally, I am expressing my desire to bridge all types of programs within a given context. It is my hope that my architect is always performing with a social agenda. An architecture that connects the public, the community, and the neighborhood.

On Tuesday, October 26, Bjarke Ingels spoke about B.I.G.'s process of designing an architecture that is both programmatically rational and formally beautiful. This lecture was very helpful for me as I begin to investigate the ways in which my Artitecture can respond to issues of programming. After the lecture, I created the above diagram to combine the rational of B.I.G. and the exploration of my theory studies.