designing MEANING

Abstract

In this article, I want to discuss the role of certain expressive, thoughtful, and poetic moments occurring in architecture. In doing this, I aim to highlight the therapeutic dialogues between thoughtful moments in built space and the quality of experience for the building’s user. To me, a cognitive understanding of a place, be it historical, contemporary, or forthcoming knowledge is the most meaningful tool in designing architecture for the true nature of a specific culture. Social poetics or building–user dialogue must be considered in making architecture more meaningful for its users. Only by creating links and connections between a place and built space can a social dialogue exist in architecture. In this article, I explore Diller and Scofidio’s, Le Corbusier’s, Loos’, Kahn’s, and Koolhaas’ work related to these issues.

Meaning and Expression

The human nature of a culture craves moments of meaning in their local architecture. Meaning can be embedded in many forms of architectural intervention. Design that realizes this notion by reflecting its users in solving simple problems of form and function can hold meaning and leave impressions, thus creating memories with the user it has engaged. For example, in Louis I. Kahn’s 1974 Lecture and Walking Tour discussion at the Fort Wayne Art Center Dedication he states:

The person who senses architecture as a great expressive need and thinks nothing of the profession except in what way he can be in a society of others like himself, cannot really build a school with twenty classrooms the same size looking the same way when he realizes that every room has a different response, a different ring to it, a different tonality, a different colour.1

In the above statement, Kahn, who is internationally recognized for his architectural brilliancy is demanding his architecture to respond to both the natural elements, in this example the path of the sun, as well as the psychological position of the users of his architecture. For Kahn, a building that does not recognize each space as having a unique problem to solve, fails to meet the demand of its user. Kahn is emphasizing the importance of connecting the user to the place through architectural intervention.

In this account of Kahn’s theoretical rhetoric, I would like to draw attention to the central values he places on his architecture and ways in which my thesis appropriates such ideas as precedents for good design practice. First, Louis I. Kahn always approached his design problems from an artist perspective; “If I could think what I would do, other than architecture, it would be to write the new fairy tale...” 2 By thinking from the vantage point of an artist, Kahn was able to focus on the importance of meaning in his designs. A dreamer, and a poet of experience, Kahn is highlighting the importance of the expression of imagination. As it is in the imagination that the airplane, the locomotive, and the architecture has been born.

Secondly, Louis Kahn is well known for his command over natural day lighting as well as his use of shadows in creating space. Nature does not choose…it simply unravels its laws, and everything is designed by the circumstantial interplay where man chooses. Art involves choice, and everything that man does, he does in art. 3 Using his knowledge of the powerful meaning of light, Kahn is declaring nature’s circumstance, as a personal medium of design. Kahn is using an expression of knowledge to embed meaning into his architecture.

Embedded in such moments one can began to realize the power of artistic expression on the psychological experience of a building’s user. When a designer expresses a true understanding of the elements at hand, the quality of the user’s experience is affected exponentially.

The architect by his arrangement of forms, realizes an order which is a pure creation of his spirit; by forms and shapes he affects our senses to an acute degree and provokes plastic emotions; by the relationships which he creates he wakes profound echoes in us, he gives us the measure of an order which we feel to be in accordance with that of our world, he determines the various movements of our heart and of our understanding; it is then that we experience the sense of beauty. 4

Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture realizes the ways in which the placement of each geometry and architectural element can have an effect on one’s perception of a place and the beauty that is embedded in the architecture. Often considered to be a sculptor of Modernism, Le Corbusier understood the ways in which thoughtful expression could inform a user of his buildings to have emotional connections to the architecture. Successful expression may be most evident in the Notre Dame du Haut, or Ronchamp where Le Corbusier uses the plasticity of concrete to acoustic excellence. The chapel walls are given a concave curve to amplify the voices of the choir. This acoustic gesture combined with the poetic placement of varying apertures creates a space that is as close to divinity as Leonardo da Vinci’s last supper.

Unfortunately, such understanding and expression was not successfully considered in Le Corbusier’s master plan for Paris. In his proposal for a new Paris, a tabula rasa was to be employed in which every building was to be destroyed and replaced by countless buildings that appeared to be exactly the same, with every space in between the buildings looking exactly the same. This proposal left Paris with an emotionless objectified architecture. Had Le Corbusier’s design been constructed, the city of Paris would not carry the romanticism and embedded richness of art and culture it has sustained for several centuries.

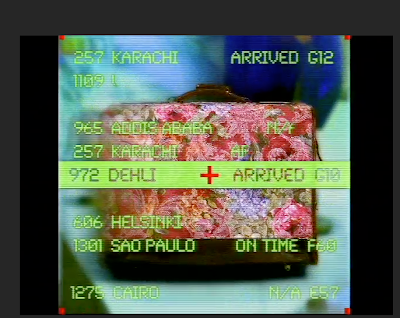

Thoughtful Technology

In relating the ideas of the Modern legends of the past to a more contemporary theory, I feel it is important to look towards the new architecture and sometimes non-architecture of Diller, Scofidio and Renfro. With a passion for technology and architectural space, Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio have set new standards for the ways in which architectural interventions find a meaning with their audience. Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio have been working as installation artists since 1979, and in 1989 began taking their theoretical play to an architectural scale. The sterile corridor is a space peculiar to the regulatory nature of contemporary air travel. It is a featureless non-place between jurisdictions, between the place left behind and the one about to be entered, a space in which diverse travelers share the status of world citizens in limbo. 5 In their 2001, Travelogues installation at Terminal 4 at JFK Airport, New York, Diller and Scofidio believed that a technology driven interpretation of the old Burma Shave signs could transform the user’s experience far more effectively than any conventional or decorative element. The digital installation is an attempt to relieve the normal boredom of walking through the corridors at JFK Airport. In this project, Diller and Scofidio are recognizing the ways in which technology can be substituted for conventional aesthetically driven architectural interventions. This is a technique that relates to expression of the current times. Diller and Scofidio are embedding cultural meaning in their work by using contemporary technology to relate to contemporary culture. Diller and Scofidio’s the I.C.A. in Boston carries the same tonal strategy at an architectural scale. In the I.C.A., Diller, Scofidio and Renfro established a significant connection to a younger population of users. Rich with technology, expression of materiality, structural exploration, and artistic gestures, this building holds meaning with the youth population in the city. Although the building has reached an iconic stature now, the I.C.A. was not popularized simply because it is an iconic building, but because it brings a new language to Boston’s archetype. The Institute for Contemporary Art building is a timestamp of a specific generation of people; with this embedded relationship will come an everlasting dialogue between building and users.

Poetics of a Place

Congruent with the contemporary works of Diller Scofidio and Renfro, Rem Koolhaas is another credible architect making new passes at older theory. In his retroactive manifesto, Delirious New York, Koolhaas aims to reveal an architectural theory that glorifies and amplifies the ideas behind what makes New York City so fascinating. “The Grid makes the history of architecture and all previous lessons of urbanism irrelevant.” 6 As revealed in Delirious New York the success of the city has always been a seemingly rule-less archetype bound by nothing more than a gridded street system. Far different than any city of its time, in Manhattan starting in 1807, builders were able to develop a new system of formal values based on varying types of buildings stacked next to each other regardless of material, function, or size. Such a diverse system made easy the opportunity for all types of people to find a meaningful connection to the architecture of the city. “Manhattan is forever immunized against any (further) totalitarian intervention.” 7 The two-dimensional rigor of the new grid created an undreamt of freedom for architects, bankers, builders, and politicians of the time. As a result of such freedom, the city is now diversely layered like a bookshelf aligned with very different religious manuscripts.

If the Bible, the Quran and the Torah are all next to each other, what happens in between these spaces? Rem Koolhaas’ design team: OMA and its research driven counter part AMO seeks to answer this very question when they execute a design. Armed with a contemporary view on the process of designing, OMA uses data driven analysis to literally embed their buildings with informative meaning while establishing an unquestionable dialogue between their architecture and the users of their built space. Such methodologies for creating spaces are newly becoming the second wave of designing with Modernity as the form always follows function, only with a slightly expressive quality.

Opposing Vignettes

In order to solidify my ideas, I would like to compare two moments of dichotomy in architectural theory and practice.

In 1908, Adolf Loos’ Ornament and Crime defines an important moment for the meaning of expression in architecture.

I will not subscribe to the argument that ornament increases the pleasure of a life of a cultivated person, or the argument, which covers itself with the words: "But if the ornament is beautiful! .....” To me, and to all the cultivated people, ornament does not increase the pleasures of life. 8

Loos is writing with personal angst towards his father, a sculptor who specialized in commemorative monuments and architectural decoration in the early 1900’s. I feel it is important to recognize both the time period and the parameters in which this piece was written. Had Loos lived to experience the nature of expression in our contemporary architecture, he may have skewed his words to support thoughtful expression. I agree that meaningless ornament should be a crime. I disagree with Loos’ ignorance to the potential for knowledgeable expression to sustain a dialogue between the architecture and the user.

Contrary to the ideas of Loos, in 1969, Louis I. Kahn discusses the ways in which ornament can be conceived of having a meaningful purpose.

I feel that the beginning of ornament comes with the joint. The way things are made, the way things are put together, the way one thing comes to the other is the place where ornament begins. It is the glory of a joint, which is the begging of ornament. The more a man knows of joint, the more he wants to show it. The more he wants to show a joint the more he wants to show the distance. And if he wants to have the show of the distance, he wants to exaggerate and caricature things, which ordinarily are small. The beginning of ornament lies also in the challenge against the elements. 9

Here one can realize evidence of ways in which Kahn’s architectural expression is justified in helping the architect to teach the public tectonic understanding through artistic expression.

I feel it is important to draw attention to the two above ideas because they are so different. The contrast is presented to express the nature of opinion, for meaning lies within the opinions of an audience. Designing meaningful architecture is almost always based on place and perception.

Closing

Where modernity has been proven to be a scientific method that can satisfy flexibility of space and perspectival gestures that sometimes comfort photographers more than users, it cannot theoretically grow towards human dialogue without thoughtful expression added like architectural condiments supplementing a modern salad.

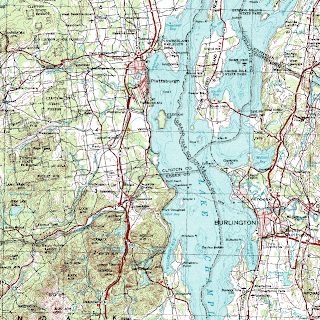

There are multiple moments in time when a building can bear significant meaning. The first moment is that of the expression of a place by the architect, the designer, or the person who conceives the building. The second moment is for the user, where one can find social dialogue within the building. This could be something inside a framed view, a detail, a texture or any number of expressive gestures in the architecture. And the third moment is on a larger scale; it belongs to the culture of a place, it is the fulfillment a culture finds within a building as a symbol or an icon. The tertiary and the secondary cannot exist without the primary. There cannot be a building that means something to a culture without it having an expressive meaning with the architect first. It lies in the process of making, that meaning can be embedded. If that process never occurs, that expression never made, the reflection never established, then the building can never become a meaningful space for the user. Therefore it is the responsibility of the architect to embed these expressive, thoughtful and poetic moments into the science of construction. The architect has to be conscious of use of materials, and of the way the building sits in context. If the site is an urban context, the architect should look at ways in which the design can respond to the surrounding buildings. If the site is a rural condition, the architect should be concerned with how the building sits within the land and how topography can play a significant role in this building’s performance. Also, the architect should focus on what the long-term cultural affects of this building being placed on this specific site are. If meaningful ideas are never conceived of or considered in the process of making a building, then the building will therefore become a static object, a thing that has a short-term function, and no connection to its users, place or surrounding culture.

1. Wurman, Richard Saul. What Will Be Has Always Been The Words of Louis I. Kahn. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1986. p. 248

2. Kahn, Louis I.. Conversations with Students; Architecture at Rice 26. Houston: Princeton Architectural Press, 1969. p. 27

3. Ibid. 2.

4. Le Corbusier. Towards a New Architecture. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1928. p. 1

5. "Travelogues." diller scofidio + renfro. Available from http://www.dsrny.com/. Internet; accessed 22 November 2010.

6. Koolhaas, Rem. Delirious New York. New York: The Motacelli Press, 1978.p. 20

7. Ibid.6.

8. Loos , Adolf. Ornament and Crime. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1908. P. 29

9. Twombly, Robert. Louis Kahn Essential Texts. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2003. p. 60-61